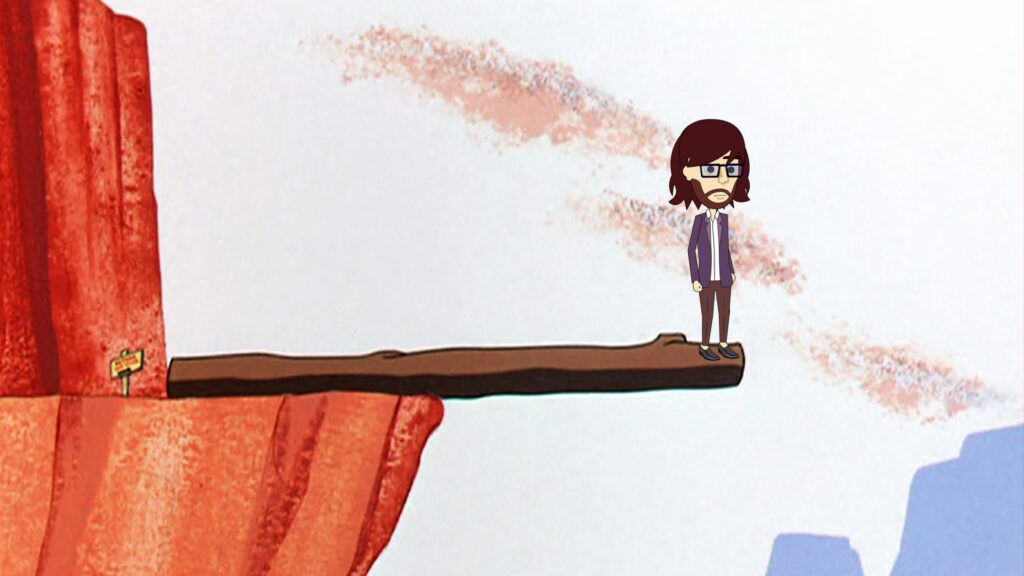

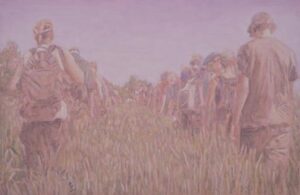

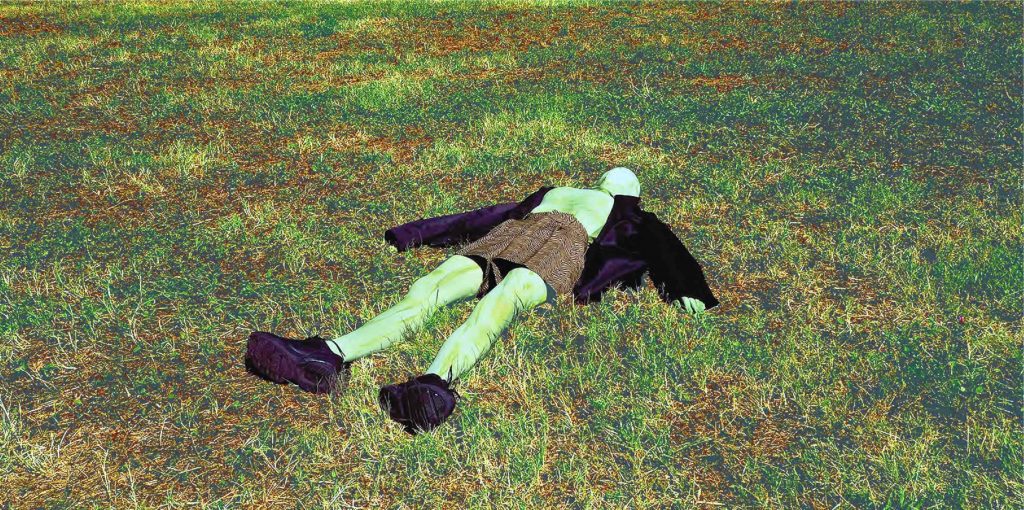

A. Sokurov e Marianne, Francofonia, A. Sokurov, 2015. Courtesy Lo schermo dell’arte film festival.

A. Sokurov e Marianne, Francofonia, A. Sokurov, 2015. Courtesy Lo schermo dell’arte film festival.

The Louvre set up today, inhabited by the ghosts of Napoleon and Marianne.

The Louvre empty, at the time of the Nazi siege.

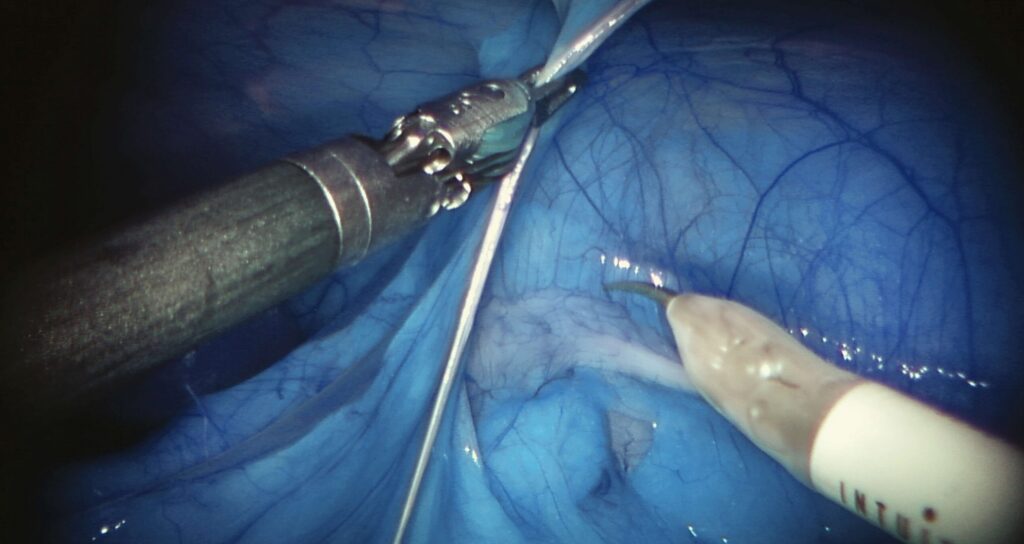

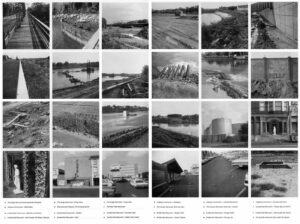

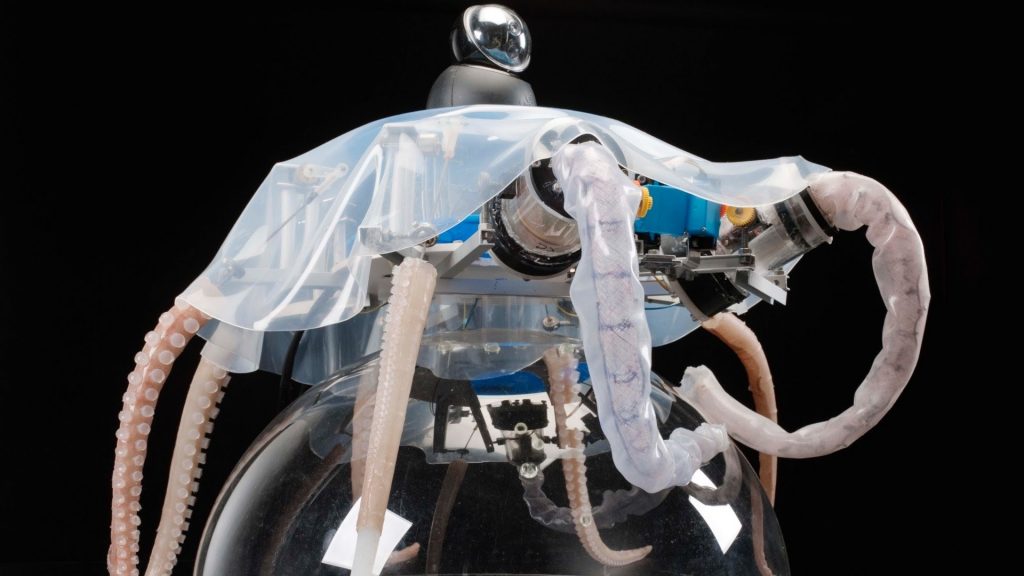

A cargo ship faces the storm to carry the crates of numerous works of art to an unidentified museum. The captain of the cargo, regretting having accepted the assignment for bad weather conditions, sends constant updates to the film director Aleksandr Sokurov, back from Paris where he has finished to shoot the movie.

«Tossing art on the Ocean is inhuman». * The reflections generated by the movie are not so different from the sensations caused by the images of the destruction of the archaeological site of Nineveh and Nimrud that the Huffington Post has defined as a «cultural genocide ‘by’ those who challenge the feelings of humanity». While Francofonia is screened at the movie theater, the reality of the recent months is broadcasted from our TVs. The reason why Sokurov had the need to use the Louvre as a way of translating our daily fears and raise awareness is explained by John Berger in the 70s: if we isolate the following text from the script of the BBC TV show, we may well believe that these words come from an interview given by Sokurov itself.

«Tonight it isn’t so much the paintings themselves which I want to consider, as the way we now see them [paintings of the European tradition which was born about 1400, died about 1900]. Now, in the second half of the 20th century, because we see these painting as nobody saw them before. If we discover why this is so, we shall also discover something about ourselves and the situation in which we are living».

– «I do not want to talk about the past. We will speak only about the present. (…)» * The museum fever.

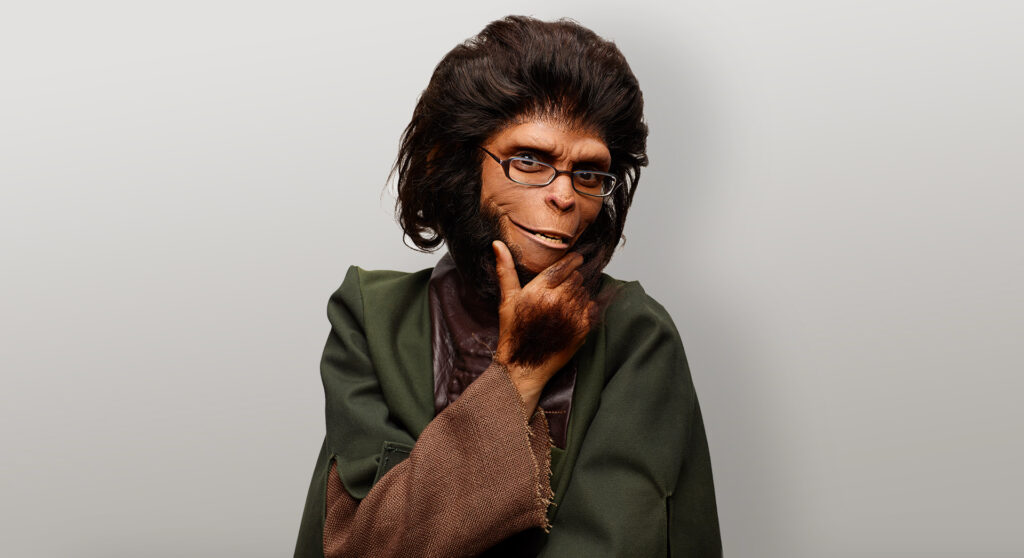

Using two locations and three different time layers Sokurov argues about the relationship between Museum, Art and War, emphasizing the human behavior to spontaneously protect the assets which contributed to the realization of their present and the consequent need of protect them by building a museum.

While the moving images are running on the screen the director’s voiceover asks questions:

«What would we be without Europe?», «What would Europe be without France?», «Who would want a France without the Louvre?» – and thus – «What would we be without museums?» *

It is therefore with some regret that we wonder about what we are really doing in Italy to show and protect the works of the artists of our generation. Can anything new become historic? Is it possible even if that still had not had time? Should a museum contribute to the evolution of artistic research or is it just called to educate and protect? What do we have to do? Finding an answer is very difficult. As Maria Vittoria Marini Clarelli, GNAM past director, writes «the museum is a place of latent conflicts, where we try to maintain balance between conflicting requirements: keeping the dialogue for the benefit of the future generation and the fruition in favor of that present […]. The museum of contemporary art accentuates these conflicts, because was born from the separation between things of culture and those of life, as every kind of museums. The difference is that contemporary art museums has also the complex mission to preserve what has just been produced, to historicize what he had not yet time to become historical, to inform before they can even explain, to be both militant and institutional» (M.V. Marini Clarelli, I dilemmi del museo d’arte contemporanea, in S. Chiodi, Le funzioni del museo, Le Lettere, Florence, 2009, p. 107.)

Since 2009, the year MAXXI opened, museums in Italy have been the subject of italian controversy, like the debate between container/content, the proliferation of numerous institutions11Cfr. A. Polveroni, Lo Sboom: il decennio dell’arte pazza tra bolla finanziaria e flop concettuale, Silvana editoriale, Milan, 2009.

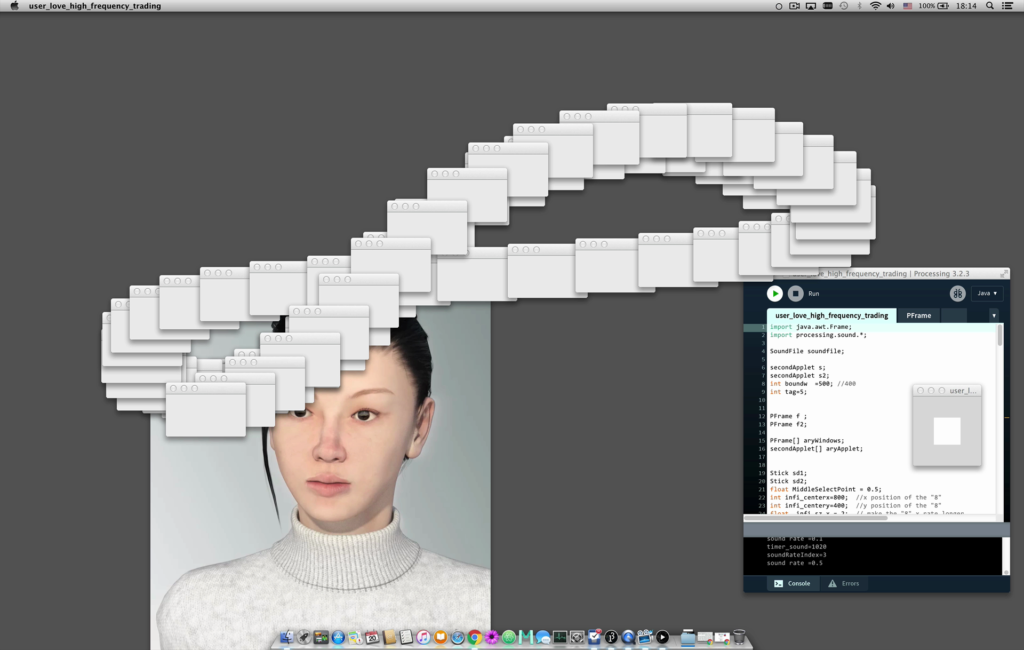

, and the current race to conquer followers and likes. As a result, we now participate to all these #name_convention where, together with useful ideas and interesting communication tips, we hear from some fanatics of “the sharing images” that in the future artists and curators will be replaced by apps. According to this, collections will thus continuously be renewed by ever changing images that, through a filter, a selfie, or an angle, will become the product of the visitors interpretation. Displayed through our mobile phone, it would be a sort of ‘users revolution’ through a democratic instrument such as the social network. This is of course an extremism, a side effect created by the raising attention to different audiences, the same attention that allowed:

– the successful “Wake up Museum”, making it more sensible to the present, once updated with new and immediate means of communication;

– to speak more and more of “relational museum” – a term which, according to the definition given by S. Bodo in his book, «intends to return to the complex nature of the museum reality, which is composed of a dense network of internal relationships – between different functions and specializations – and external – between the museum, the territory, the stakeholders and society at large» (S. Bodo, M. Demarie, Introduzione

: Perché il museo relazionale?, in S. Bodo, Il museo relazionale, Edizioni della Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli, Torino, 2003, p. XVI);

– to develop new ways to fruition the museum, given by the birth of educational departments, a relative bibliography,22Cfr. K. Gibbs, M. Sani, J. Thompson, Musei e apprendimento lungo tutto l’arco della vita. Un manuale europeo, EDISAI srl, Ferrara, 2003.

an internal staff differentiation, and its reorganization.

In ‘Relational museum’ we read about the crisis of the curatorial role and the changes needed for a team work which have as a main objective the attention to different types of visitors who are related with the museum. However, his precise and still relevant functions and, at the same time, his frustrations in public institutions, still current even if described by Lawrence Alloway in 1975 for the May issue of «Artforum», are very specific and different from those of the remaining museum team members:

- desire to get along with the artist / artists;

- the necessity to keep good relation with the arist’s main dealer or dealers;

- the necessity of maintaining collector contentment;

- taste expectations emanating from to the trustees and director;

- taste expectations of other members of curator’s peer group (L. Alloway, The great curatorial dim-out, in R. Greenberg, B. Ferguson, S. Nairne, Thinking about exhibitions, Routledge, 1996, p. 224).

All other professionals that are part of the family behind each museum allow both to facilitate and to amplify the success of the exhibition project. Therefore the work of the curator and the artist, thanks to educational workshops, initiatives, and efficient communication strategy, guarantees that the exhibition makes visible not only one of the possible messages of the art works, but also its relationship with public through tools that neither the curators nor the artists have to create a learning path with multiple levels of interpretation. If this ‘complicity’ fails, the Relational museum fails as well being misinterpreted. The consequence for the museum is either to get closed by the scientific committee or to be judged by the media only as a set of images emptied from their content. The museum cannot become mere entertainment and therefore it is necessary to reach a certain balance, moderated by the curator, between these two roles so that it can continue to support research and promotion. The communication cannot replace the fruition time, it is only the way to gather the public. Thinking about an institution as a mass media is a risk, first because, as noted by Boris Groys, media and institutions have two different though complementary roles – «The media show us only the image of what is happening in real time. Instead, the artistic institutions are places for control between past and present […]» (B. Groys, Arte in guerra, in Art Power, 2008, Postmediabooks, Milan 2012, p. 146.) – and because «Popular entertainment is basically propaganda for the status quo», as written by Richard Serra in 1973 for his video Television Delivers People.

This period, which many see as a time of transition for Italian museums, needs to be used to ensure that we put back, among the main objectives of artistic institutions, one of their primary functions, too often obscured by others: have their own identity defined by the context in which they act. This proliferation of museums would have been less boring and fulfilled with questions if each individual institution had been focusing on strengthening the identity of their site in connection with the territory.

In 1972 Franco Russoli, creator of the Great Brera, just nominated new director of the Pinacoteca in Milan, replied on the «NAC» militant magazine to this question asked by the editorial staff: «if instead of being appointed director of the Pinacoteca di Brera you were the manager of a museum of contemporary art, what kind of organization would you have established in it?».

«This is a problem that, in general terms, we have discussed during different occasions, including international ones. We discussed it at the level of ICOM and we have discussed about the Milan area.33The next ICOM (International Council of Museums) plenary session, after Shanghai (2010) and Rio de Janeiro (2013), will take place in Milan (3-9 June 2016). It is possible to read the programme online.

[…] I would never say what is the ideal museum. I think that we should not freeze in fixed standards the museums structure because, in my opinion, the museum is a tool that comes from different cultural situations and lives for different and specific needs. It should not become an instrument of cultural authoritarianism, a kind of alienation from the real culture. There are, of course, certain technical standards that we must follow – it is clear that a museum has to meet certain principles of general features – but must also have a high flexibility, not only as regards to the heritage that has been collected but also as utilization of the heritage according to specific necessities of the cultural moment and the environment in which it resides» (Intervista di Franco Russoli: Nuove strutture per i musei, in «NAC», n. 7, June-July, 1973, p. 2).

Most recently Gianfranco Maraniello, currently director of the Mart in Rovereto and founder of AMACI, interviewed by Stefano Chiodi after being named director of Mambo and Bologna civic museums, said that «When we talk about something as a ‘museum’ we run the risk of discussing idealization and forgetting the precise critical subject. The functions taken by the museum vary with respect to its environment, the underlying economies, the conventionality and symbolic values that determine its existence» (S. Chiodi, Il Museo all’opera: Una conversazione con Gianfranco Maraniello, in Le funzioni del museo, op. Cit. p. 200).

Angela Vettese, interviewed by Chiara Bertola, stresses the importance of formalizing the identity of each museum in relation to its territory because, with a political strategy, it could more easily launch relations that are extremely important for an institution of contemporary art: «Mart would not be born in Rovereto without the legacy of Fortunato Depero. The Castle of Rivoli would not be born if not close to the context of Arte Povera in Turin. The relationship with the territory is essential for anyone who wants to do an global activity: it is rooted precisely in the place from which arise the opportunity to interact with the public, including the politicians responsible for funding the group» (Intervista via e-mail ad Angela Vettese, 2006, in C. Bertola, Curare l’arte, Electa, Milan, p. 295.).

There are still many cases that bode well. Here just a few examples from museums and public institutions, promoting production of Italian artists:

– Call for curators, promoted by Mart in Rovereto. It realized a project comparing more famous with less recognized artists;

– HPSCHD 1969>2015, hosted in the Sala delle Ciminiere of Mambo during Live Arts Week 2015, with the intent of representing the entire of the same name work of John Cage and Hiller Lejaren, offering an insight on today national and international audio-visual art research;

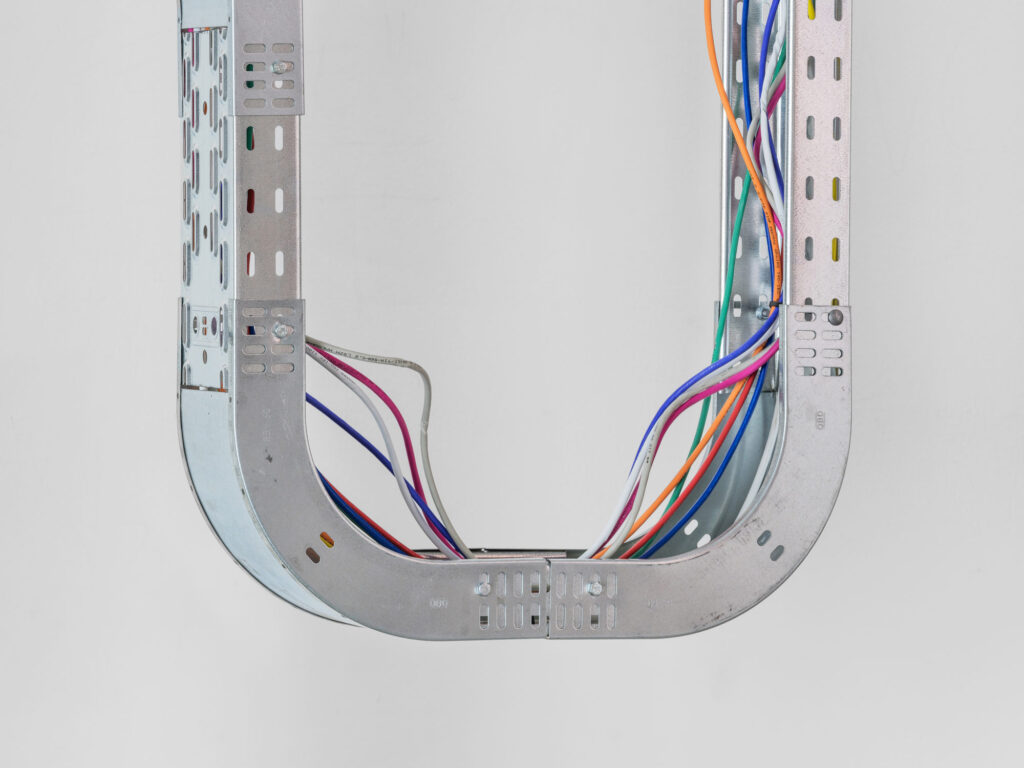

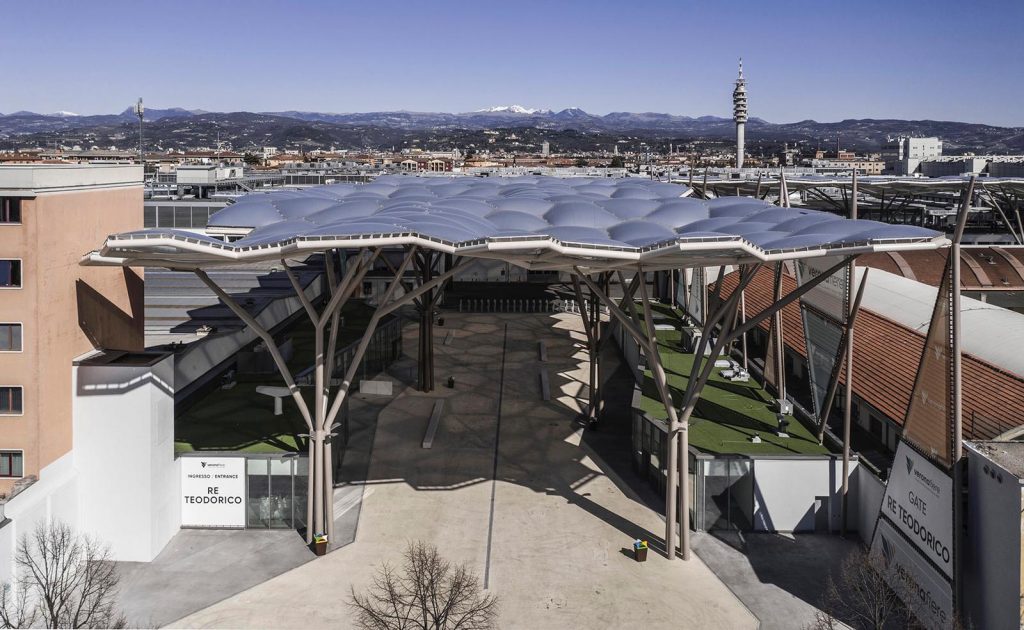

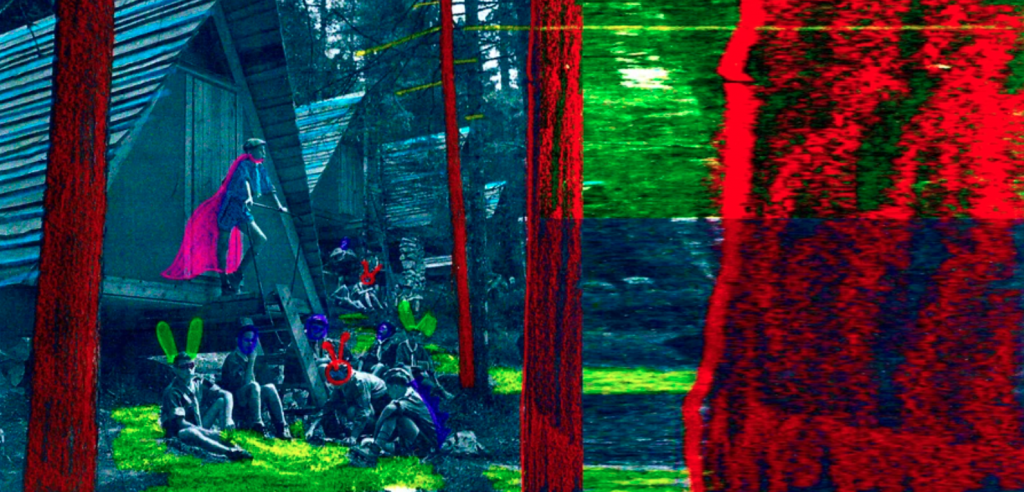

– Glitch video group show at PAC in Milan, where many different generation of Italian artists have shown their works first in Milan and then in Shanghai;

– Marino Marini Museum in Florence hosted events such as SONIC SOMATIC, a project by Trial Version and Internation Feel in collaboration with Blauer Hase and Giulia Morucchio, during the fourth edition of Helicotrema. Festival dell’audio registrato;

– MACRO, with its residency program for artists, carried out the willingness to be seen as a «workshop museum», a place of production, promotion, and cultural diffusion.

This list shows a due diligence, albeit sporadic, for the growth of the new generation, even if institutions are still too much pushing who work with sound, performance and moving images, inevitably discriminating a large number of artists.

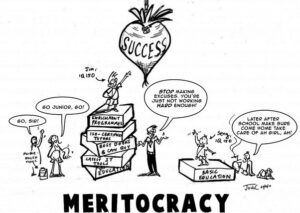

However, together with the horizontal reorganization of museums we need to put in the ‘to do list’ a revision of the scale of values of the institutions. They still prefer for their exhibitions artists already represented by prestigious galleries in order to gain the trust of international art magazines, the public, and a good number of collectors who attend these events. There is the trend to make ‘exhibitions-event’ with famous artists and to participate to social initiatives with the goal of gaining the attention of the press and selling a huge amount of tickets. When do exhibitions give space to new artists that are not still part of the art system? Do they have to end up in lower category projects with a paltry budget, or even 0 budget, forgotten by the communication teams? Perhaps the biggest problem is that only few really feel this responsibility on their shoulders, and a lot prefer either to delegate the judgment to others, or to do self-referential exhibitions never trying something new. In support of these thoughts, during the Italian Contemporary Art Forum promoted by Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci, there is a very significant proposal coming from the discussion of the table moderated by Luigia Lonardelli, which addressed the theme «Public Quantity vs quality of the proposal» in the museum context: «Combining high-level research and high-level disclosure, in the name of quality and design of the display and information tools without yielding to the one hand to the temptation of the mainstream and the blockbuster at any cost, on the other to the niche and ‘self-referentiality’, to create the “trust” that allows to take the public into new territories, without disorient him with proposals that are difficult to read. Without eliminating a priori large exhibitions, create a program that alternate them with less high-sounding projects by building a relationship of reciprocity between expectation and proposed» (AA. VV., Atti del Forum dell’arte contemporanea italiana 2015 25-26-27 settembre, Prato, 15 aprile 2016, p. 22).

If we think that in Italy we are surrounded by non profit spaces, per definition dedicated to support new fields of study of the visual arts, that do not do any research and just look more frequently to the same small group of artists, their friends, we are left with no hope. This fact makes impossible to actually implement something new, representative of our day. At the end, institutions need to:

– create dialogue with the public, thank to educational departments with a program that can gather a lot of people;

– be known and recognized by showing and producing exhibitions of international artists to create a network with important and famous galleries;

– support the production of young artists, so that we do not stop this continuous journey.

If not, what are future generations going to enjoy?

* A. Sokurov, Francofonia, 2015.