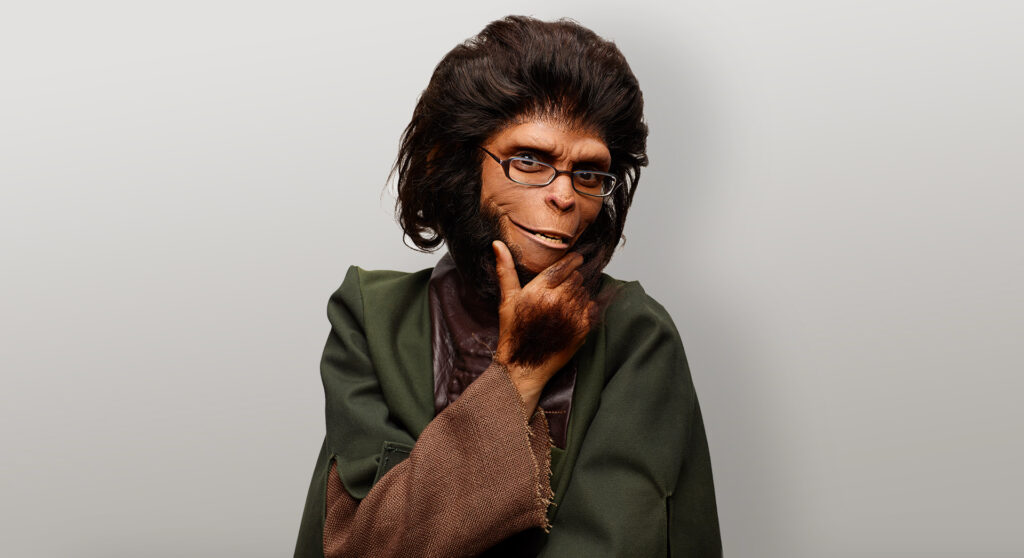

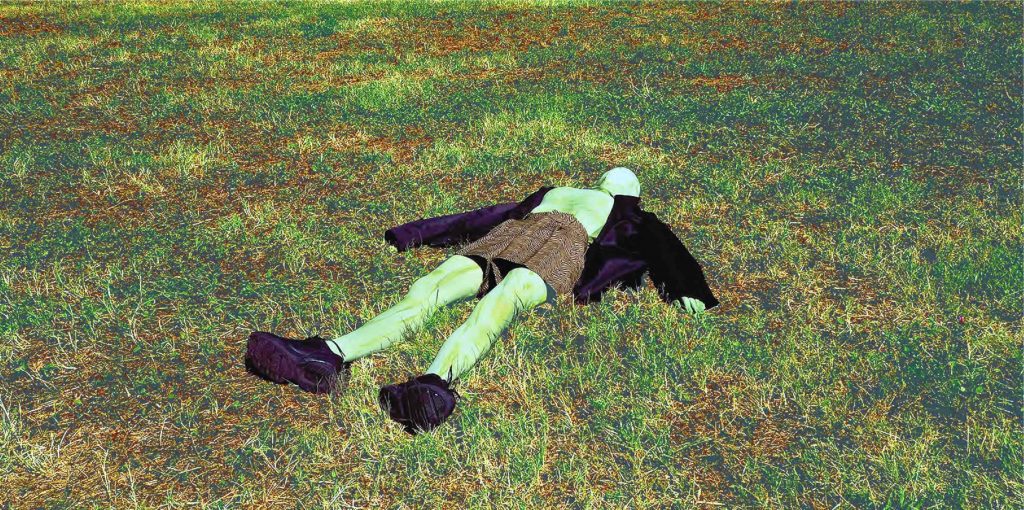

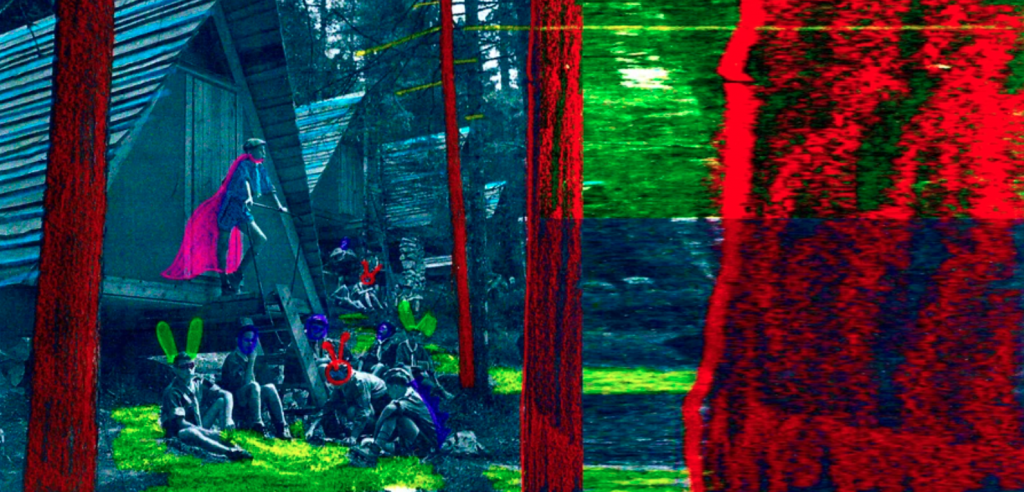

Setting the table… , Whitechapel Gallery 2019 – photo Wapke Feenstra – Myvillages UK.

Setting the table… , Whitechapel Gallery 2019 – photo Wapke Feenstra – Myvillages UK.

Myvillages is an artistic collective founded in 2003 by Kathrin Böhm (UK/DE), Wapke Feenstra (NL) and Antje Schiffers (DE). The three artists, that met at the end of the 90s, developed a practice that investigates the relationship between rural culture, from which they themselves come from, and the urban culture to which they had always related as artists. Myvillages does not have a rigid structure, allowing each of its three members to work both collaboratively and autonomously, making it possible for it to be present on multiple territories at once.

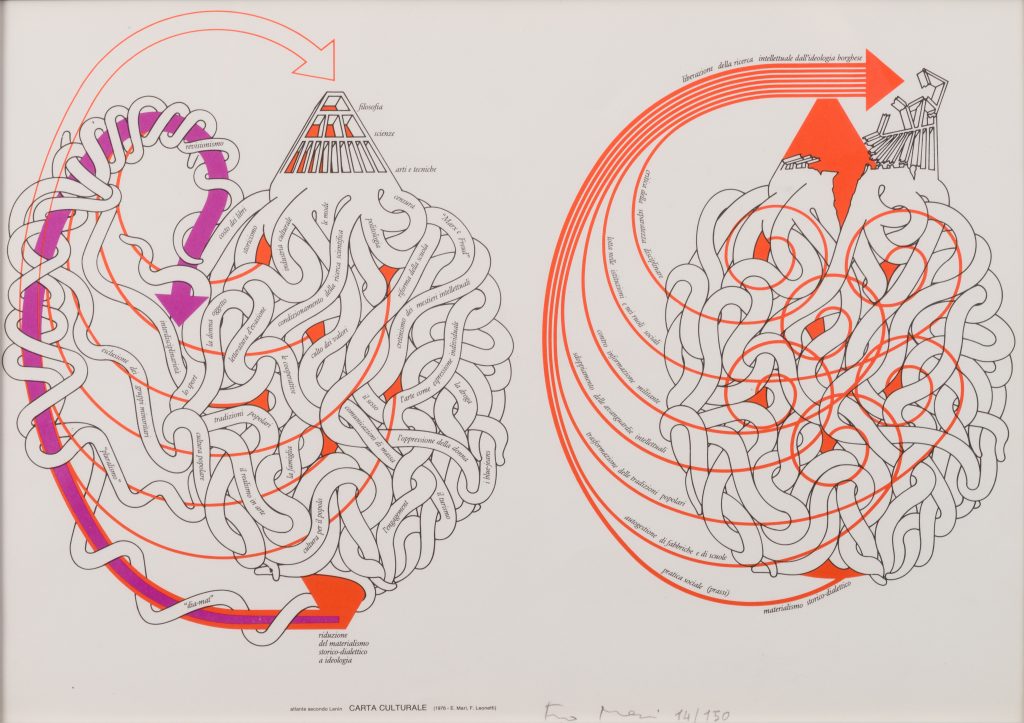

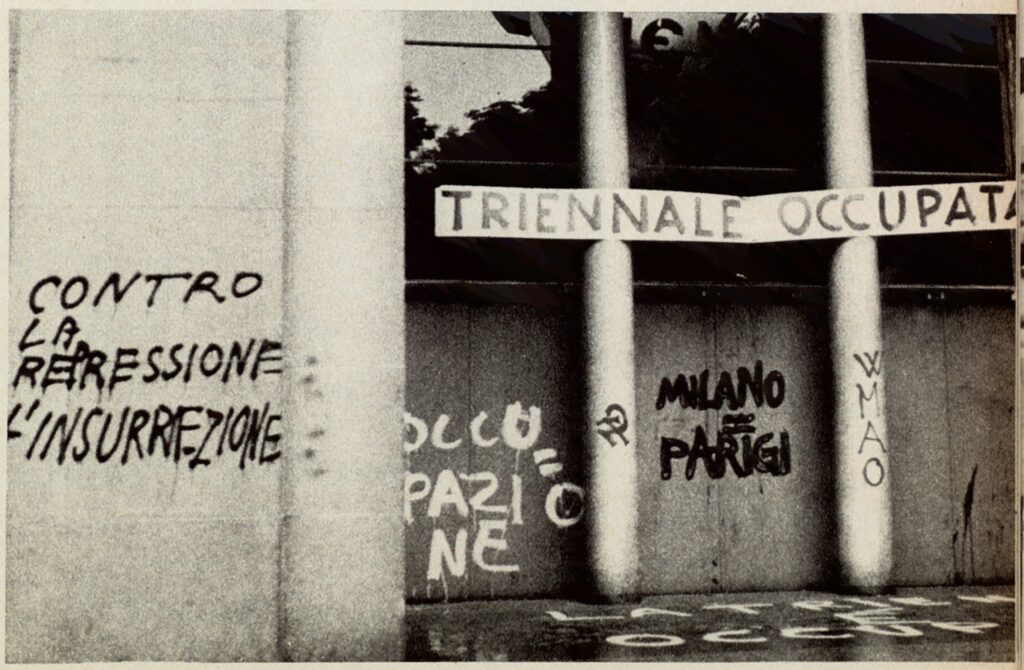

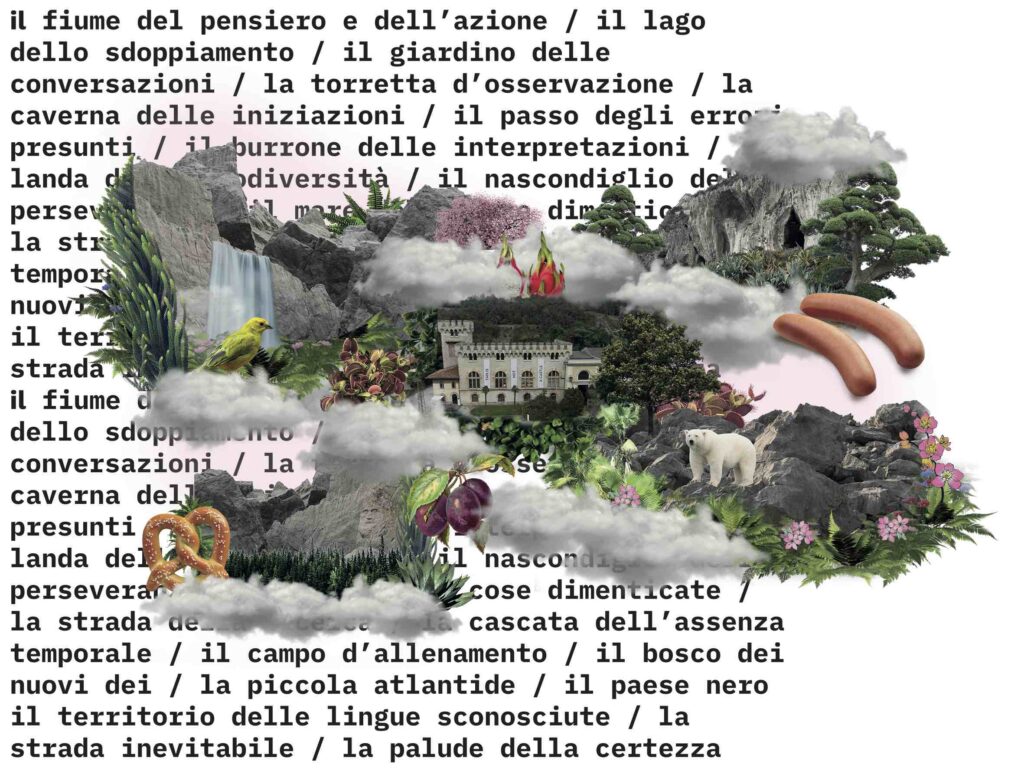

In the summer of 2019, Myvillages brought the exhibition Setting the Table: Village Politics, at the London Whitechapel, with which, earlier that year, it had also published the collection of essays The Rural, including essays by Okwui Enwezor, Hal Foster, Amy Franceschini, Grizedale Arts, M12 and Rirkrit Tiravanja among others.

Myvillages was one of the first realities to investigate, in the midst of the late 90s and early 2000s urban and digital capitalism, the evolution and relevance of rurality, giving particular attention to its contemporary needs and to its development. In the interview, Wapke Feestra speaks about the origins of the project, to later concentrate on what is one of the most urgent problems of rural culture, namely the submission to an urban gaze that traps it an a picturesque and non-productive realm. The Myvillages’ work tries to investigate and free the image that rurality has of itself, questioning its potential for growth, the possibilities for its future and the terms for fructuous exchanges with both the observing urban and other rural cultures.

Elena D’Angelo: In the introduction to your book for Whitechapel you mention that you all came from the village and decided to come back to it after studying art. In the village you laid the foundation for a series of trans-local practices, making it obvious that your choice was not a movement towards the past, but more like a leap forward, in a new version of the future that finds sustainability in direct and humane exchanges. Did you have conscience of this when you went back to the village? Or did you find the possibilities given by this practice through the village itself?

Wapke Feenstra: That’s something that I slightly have to correct, we say we came back to it, but we came back to the topic, and we came back to it as a working place for the conceptual art we are part of. All of us, all three of us, came from different art schools, shattered through Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. I [Wapke] am 10 years older than Kathrin, so I already had a gallery career and Kathrin was at Goldsmiths when we talked about setting up Myvillages. The reason was not that we literally wanted to go back to the village, but that it is strange that the culture that we grew up in was not part of contemporary art and of the cultural field in which contemporary art is playing, especially not at the end of the nineties. Back then it was very much about the urban, it was about celebrating urbanization, which was probably also about celebrating capitalism. We always had to explain our cultural background, but we felt a general preconception that brought people to think that rural culture was lack of culture. In a way you didn’t even talk back to it. But meeting other people in art that also grew up rural, made us understand that it’s also important knowledge, for everyone. So we decided to go back to all our villages and make projects there. We were visiting each other’s villages, which is where the name Myvillages came from. We begun by bringing the rural to the contemporary art field where we already were. So it’s not like we came from a village and from that village we came into contemporary art, we were part of a contemporary art scene, a kind of fresh young one, and we thought we wanted to expand the field. We didn’t want to act like there was a better and a worst culture, but we wanted to share how you can mediate and learn a lot from rural places.

Our families still lived in the villages, my sister [Wapke] still runs the farm where i grew up, Kathrin’s family still lives there, so it was part of our movements and of our fields of experience. We wanted to bring that into art, and we had to team up for it, because the rural was not very popular at that time, if not when talking about landscape and land art. Everything was also very male-centered and when you looked at conceptual art there weren’t a lot of female examples, so we really had to be our own support group in the beginning. It was very self organized at first, and to have a legal status in 2003 we started an NGO. So when we say we came back to the village, it means that we came back to it as a field of contemporary culture and contemporary art and also that we didn’t want to live if the rural was the past: it’s present, it’s alive, it’s still there and it is happening.

Elena D’Angelo: You mentioned this idea and image that the urban has of the village: a rural pastoral life, centered on nature and landscape. You, on the other hand, have placed rural and urban on the same level of cultural relevance…

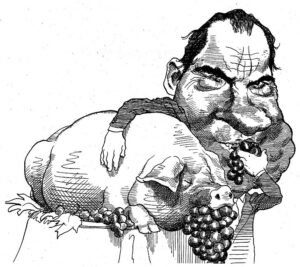

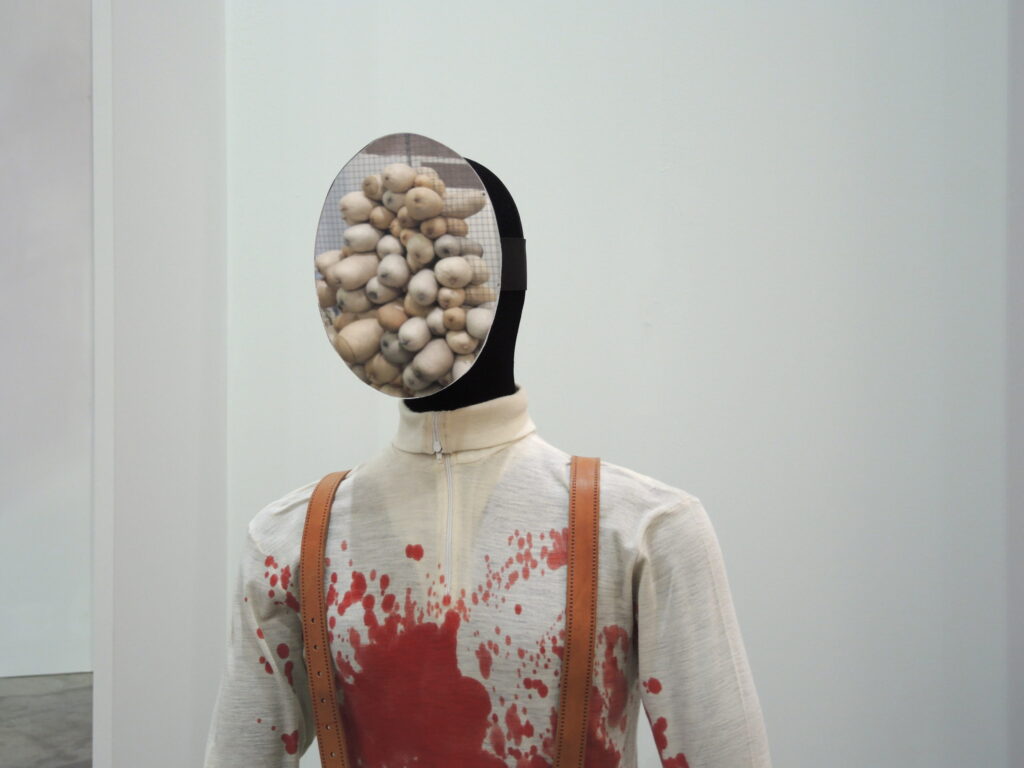

Wapke Feenstra: Yes, there’s an interesting discourse about it in the book Images of Farming (2010) that Wapke edited with Antje Schiffers. It concentrates on Dutch and Flemish paintings that have to do with rural culture, like those of Bruegel or Frans Hals. In that case the rural also comes out as a warning: it is romanticized, but it’s also something you don’t want to be part of, it’s rough. We now think that the works of Bruegel are interesting, but they also show a lot of bad behavior, and rich people, Flemish and Dutch salesman and such, wanted to have those paintings to underline their well-being and their high class by contrast. But still it was painted, so farming is part of art history, and also rural culture, farmers culture, village culture are part of art history, and despite this they would never be considered as examples of high culture. Either they are romanticized and utopian, or they are something you don’t want to be part of.

Elena D’Angelo: I don’t think there’s an actual image of contemporary rural life either, but I feel like you are working on that. You try to give an understanding of contemporary rural life, and in many of your works you try to put different rural communities in contact with each other, despite their different backgrounds

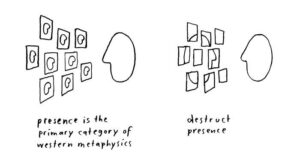

Wapke Feenstra: It’s interesting, there is also something about it in the book: it’s about the “gaze”. There’s always a game on the rural, it is never about touching it, or having a relationship with it that is one to one, but it is mostly about building images, and gazing: when you enter the rural, it is so diverse and rarely authentic. Most people we meet in the art world come up to us and talk about their country house, a holiday or hiking: which is all leisure. I [Wapke] grew up on a farm, for me rural culture was about coming together, having common moments related to the harvest or the times of the year, and those moments were related to moments of agricultural production. Then industrial production came and that changed social life in the villages, but now the rural is mainly connected to this image of leisure, which means it has to create an image of itself that is consumable. When leisure comes in, the way a landscape looks, the way a rural culture looks is a production for contemporary consumption. When the rural becomes something for the urbanized few that come to it for holidays, it stops being a place for production, it becomes a place that serves us with the images we need. We are not actually interested in what is really produced in the rural, which is for example farming, mining, but also landscape as a kind of side product. When tourism comes in people produce images that feed it. When you go to a village or a farm, if it wants to attract tourism, it freezes an image of a certain kind, that is popular for the tourists. But if you think it’s an alive, productive place, you realize that the things that you freeze for leisure actually have to do with production, although production has been taken away from them. So now they are just a sculpture, a picture, or something that is at your gaze’s disposal. There is a lot of gazing at each other from the rural to the urban and the other way around, and our concern is to break that up, so that we can learn from each other. We don’t go there and teach them about contemporary art, I think contemporary art is much richer if it opens up to the rural and there is a culture exchange, so trans-local, from one rural to another, but also from urban to rural. And I must say that the exchange from urban to rural (and the other way around) is what we mostly have to organize, and that we help facilitating exchanges from rural to rural, but that is, in a way, easier.

Elena D’Angelo: Trans-local exchanges are at the core of your practice, they are visible in projects such as the eco-nomadic school, the permanent international village shop or one of your earliest projects, the 2005 Village Convention and Bibliobox. Have you found the rural to be enough of a common ground to implement exchanges between different cultures and countries?

Wapke Feenstra: Mostly it is. People from a village will go to another village and they’ll have a lot in common. For the project Farmers and Ranchers (2014) for examples, young people from a ranch and young people from a farm had to talk to each other about their daily life, and they also made a script about it. By meeting, by organizing these meetings, you get contrasts, of landscape, of daily life, but you also have a lot of the same rhythms and a lot of the same obligations, you have similarities in the contact to earth or to your place, or in the fact that you know how to treat an animal that is five times bigger than you. It’s the same if you live in the mid-west of America or in the North of Europe. But the issues that we are interested in come up also from local contrasts, and also from people talking about their daily life, what they do, what is important to them and then put it next to another situation, so this contrast of places is very important to us. You don’t want to do a voice-over of meetings, you really want them to happen.

We also work through The International Village Shop. We often discuss with people about what they want to represent, how they want to be seen, as that is a really important question. That you take the power over the imagination of your culture. Sometimes it is a playful thing to co-design new goods together. In the international village shop we can make a souvenir with a group of villagers and then, when we go to another country, through this souvenir we can tell stories about your village.

So there are different ways of working trans-local. We bring people together, we make objects with people and bring them to other places, and then we also bring different objects together, in a shop, sometimes we teach people, museum-attendences and villagers, to tell the stories of the other villages. So there is a lot of playfulness and humor in this meetings as well. But at the end we question the issue of a local identity. We do this with institutional shows and organise rural meetings through the eco-nomadic school, but that is mostly limited to Europe. We of course can’t do meetings with somebody far away because it would be too expensive, it’s not easy to bring people from Russia out of their country, but we do make projects with them, we make ceramics with them, we can draw a logo with them, we can make a film with them, so there are many ways to make this trans-local interaction possible. It is about questioning things together, open up identities and see your village anew, by saying “what is a local skill? What is a local narrative you want to tell us? What is a local resource?” Sometimes it is working with clay, sometimes it has to do with a big machine they still have from 100 years ago. One village had this flax industry, but they didn’t have the machines they needed for production, until elder people from the village said they knew how to do this flax harvesting by hand and they taught the young people. It’s very custom made in a way, but it is always about this democratic or grass-rooted way of making images of yourself, and also questioning together how you are seen and how you want to be seen, what are local skills and what are local resources, and how you want to go on in the future.

Elena D’Angelo: Your intent to put under discussion the cultural hegemony of the urban is not only visible in your practice, but also part of the way you explain your objectives as a collective. It is sometimes necessary, however, for you to have moments of confrontations with the urban with means such as your website, your books, or your exhibitions. What is your strategy when sharing content with the urban? How do you fight the exclusively “pastoral” image that urbanized culture so often has of the rural?

Wapke Feenstra: That’s dense to bring back, you go here, and then back, it’s never a straight line. We are all part of the art world. From the mid nineties we started to say to people yes, I wish to work on this farming and village things with you. We worked with curators when they invited us, but almost nobody was really interested in working rural or on rural topics at that time. So at first we had to organize our own group which we called Myvillages: it was in 2003, when the broad band came to Europe, and it was the first time we could send images to each other. Before then it was impossible to work from different locations or from a non-location like a village, so what we did to launch our group in the art scene was send e-mails to our friends, saying that we were having an event, a small cinema in a barn in a village for example, and really it was just us, a few family members and the people from one village that came along. That’s where we started, and then of course we got some attention from the art world because we were a part of it, and we got possibilities to be part of group shows, then we got funding to take people to places. But the idea of representation remains a huge issue, because questioning the representation with people is part of our work. The openness of this discussions also has to be in the exhibitions, you have to learn how to be with it, and you also need to learn how to fail with it. Because if the contemporary rural is not part of the art world than it keeps giving a fixed image, and it is dangerous that there is no movement in the way the rural is imagined, it gets isolated from cultural production and that is not what we want. We want to raise a question. And we want to let you open up when you visit the show. So that’s interesting to do. The easier way is doing a lecture, or a performance, a theater play or a film. An exhibition is a real problem if you want to work rural, because exhibitions are not performative or time-based. So I [Wapke] went through an exhibition crisis because, how can we represent people? You know the one to one situation is no problem, but staying in the one to one is not enough, we need a more open representation. We work a lot with co-creation, with amateurism, we try to bring in different levels of conceptualization but also this kind of distaste, or taste thing, so this question is on the table, we give no answer, but we want to give an experience to the audience. Bringing it back to the art world is almost easy when you stick to the rules and think “ok I am an artist and this is art”, but if you really think about a good, open representation that would work also for a broad audience than you really challenge yourself. We had to learn a lot and teach a lot. I see it as my task to represent something so that the people that were with me are happy, I have to think so much about representation in this sense and in the end, we do want to bring it back to the art world, but not by answering questions, but by raising them. When you do participatory work you have to feel that the people you have worked with still own the thing they made with you. And you can always tell, by the way they move in the space, if they still own it. If they point at it, they are proud of it, they touch it, tell the story behind it, we are happy. It would make us very nervous if our colleagues would say that it looks fine, but then the people we worked with come in and feel distant. It is a big responsibility, they will probably not work with other artists in their life, and they gave us images, they gave us their story, they’ve shared their time with us. So the best thing that can happen when you give it back to the institutional art world is seeing that the rural still owns it.

Feenstra Wapke è artista e scrittrice. Nel 2003 ha cofondato con Kathrin Böhm e Antje Schiffers il collettivo Myvillages. Nel 2019 lavora a “Boerenzij” con TENT-Rotterdam (2018-2020), “Setting the Table: Village Politics” con la Whitechapel Gallery di Londra e con la Biennale di Istanbul presenta Potato Growers (2019). È editrice con Kathrin Böhm di “The Rural”, pubblicato da MIT Press e “Whitechapel Gallery London” (2019). www.wapke.nl www.myvillages.org

More on Magazine & Editions

Magazine , AUTOCOSCIENZA - Parte I

Appunti per un’estetica ecoqueer

La queerness nella rappresentazione della Natura attraverso le opere di Yuki Kihara, Zheng Bo, Kuang-Yi Ku e Mary Maggic.

Magazine , AUTOCOSCIENZA - Parte I

Decentrare l’agency umana

Le tecnologie immersive dei Marshmallow Laser Feast per un’empatia post-antropocentrica.

Editions

Earthbound. Superare l’Antropocene – 2° Edizione

Come sfidare l'Antropocene? Cosa s'intende con Maschiocene? Che ruolo hanno gli studi di genere nella discussione?

Editions

Earthbound. Superare l’Antropocene

Come sfidare l'Antropocene? In che modo arte e filosofia possono contrastare la devastazione ambientale in atto?

More on Digital Library & Projects

Digital Library

Il tempo delle meduse

Arte contemporanea ed emergenza sanitaria globale: un testo dell’équipe curatoriale del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

Digital Library

Ne Quid Nimis. Sull’opera di Walter Swennen

Prefazione di Luca Bertolo.

Projects

Earthbound. Ecologie di genere – Il video

Il video del talk "Earthbound. Ecologie di genere" in collaborazione con TCC e Careof

Projects

Earthbound. Ecologie di genere

KABUL ft. Carof & TCC

Iscriviti alla Newsletter

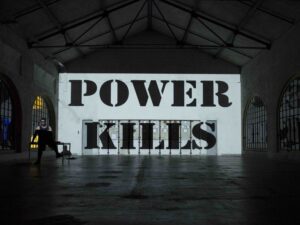

"Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. But sharing isn’t immoral – it’s a moral imperative” (Aaron Swartz)

-

Elena D’Angelo (1990) is a freelance producer and copy editor. She holds a BA in Art history for the Milan State University and an MA in Visual Cultures and Curatorial Practices at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. She has worked as a producer at Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, having the chance to organize exhibitions and projects for artists such as Anri Sala, Hito Steyerl, Nalini Malani and Cécile B. Evans. She is currently collaborating with Mattatoio, Roma, and is a partner of the online video archive instudio.

KABUL è una rivista di arti e culture contemporanee (KABUL magazine), una casa editrice indipendente (KABUL editions), un archivio digitale gratuito di traduzioni (KABUL digital library), un’associazione culturale no profit (KABUL projects). KABUL opera dal 2016 per la promozione della cultura contemporanea in Italia. Insieme a critici, docenti universitari e operatori del settore, si occupa di divulgare argomenti e ricerche centrali nell’attuale dibattito artistico e culturale internazionale.