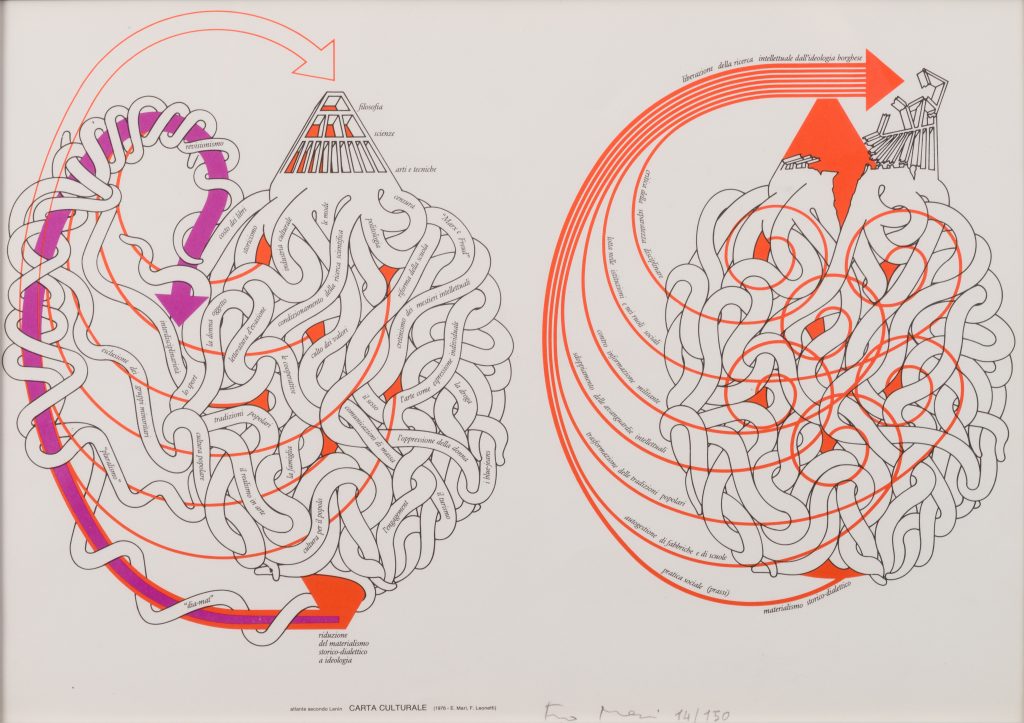

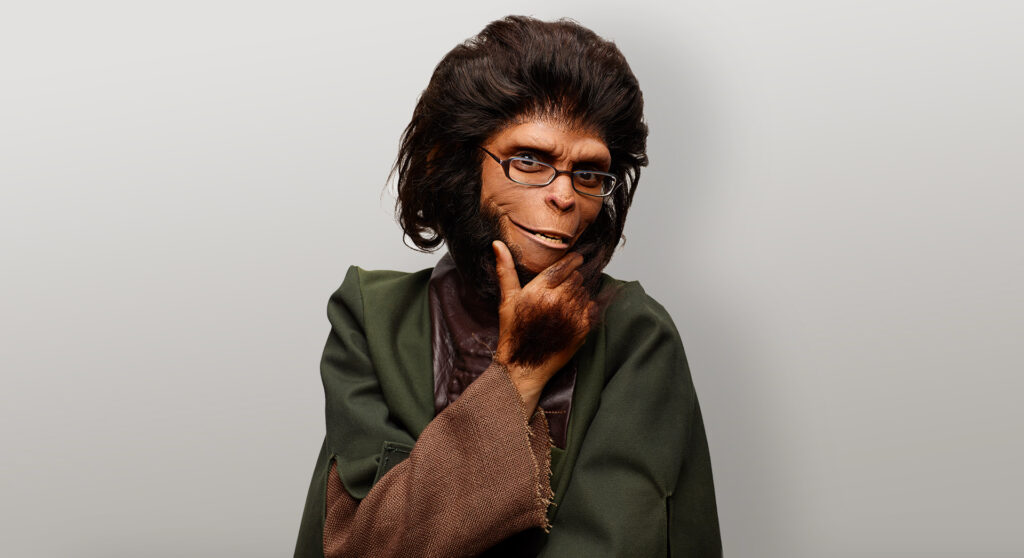

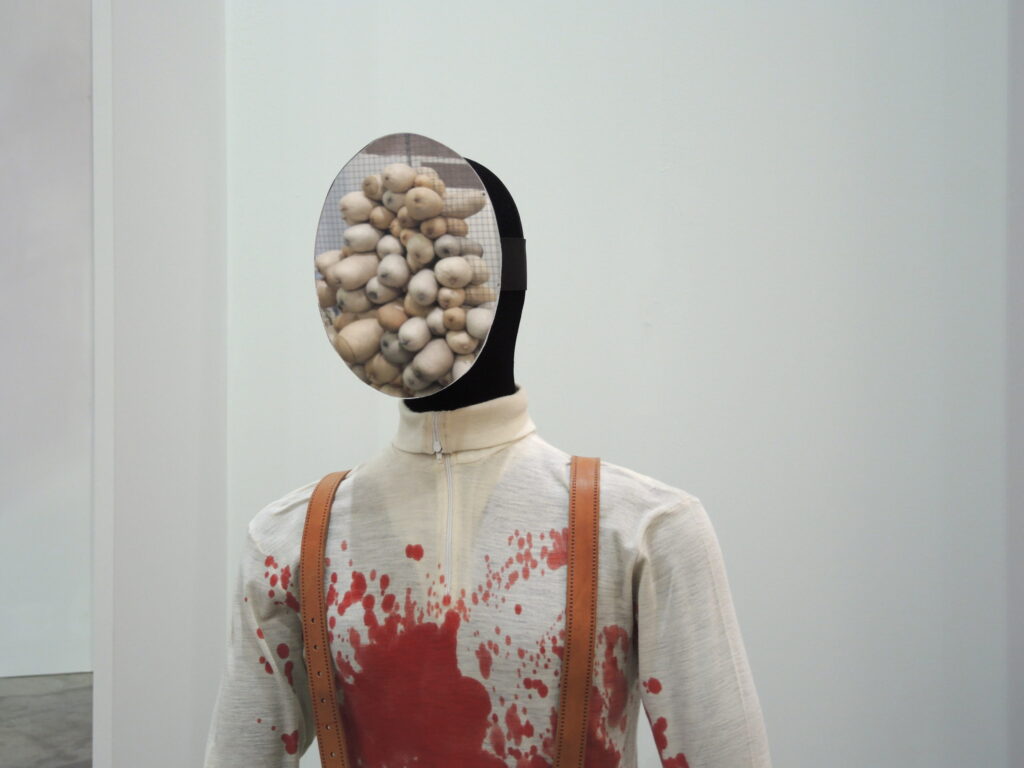

Katarzyna Kozyra, “Homo Quadrupeds Blue”, 2018.

Katarzyna Kozyra, “Homo Quadrupeds Blue”, 2018.

http://www.postmastersart.com/archive/kozyra19/kozyra19_direct.html

«My dad bought me a dog once | Don’t even ask me what I had to do in order to get it | And after a while | I started to love that dog more than I loved my dad | And once, instead of calling the dog by his name: hey, Hugo, come to me! I said: hey, kid, come to me! And so my old man lost his shit completely | He stood over me like an SS soldier and said: What the hell is this? Why are you calling a dog a kid? You are going to give me a grandson, do you understand!? | This ass of yours will give me a grandson, is it clear!?»

(SIKSA, Tato, kup mi psa (Dad, buy me a dog), Stabat Mater Dolorosa, 2018)

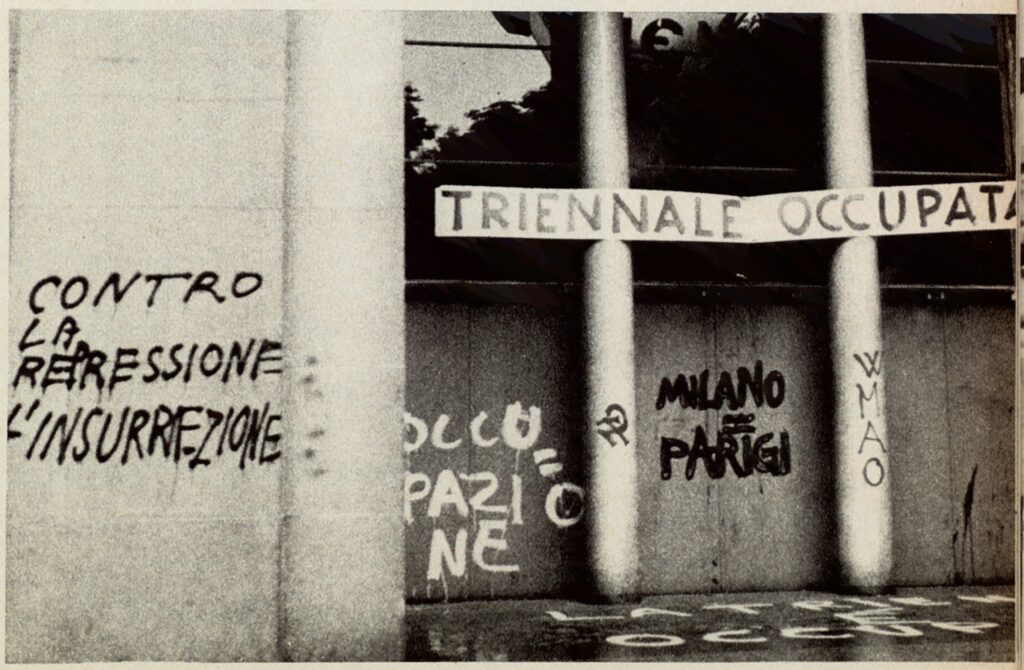

«This is my blood and this is my body – hands off!» one of the red spray paint messages on the Metropolitan Curia in Warsaw attracted watchful attention of passers-by. Other, equally significant notice, said “No more hell for women”.

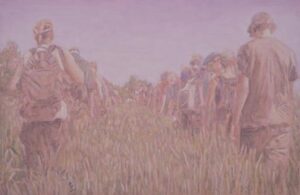

It was in Poland in 2018, when a female part of a country – shocked, humiliated and raging – took on the streets again, to fight for the basic human rights. The governmental project “Stop Abortion” (ban on abortions even in the case of severe fetal defects), pushed through by Church and religious fundamentalists, was about to be reconsidered by the government. But the situation was disheartening already back in 2016, as noted by France24: «Earlier this year, an official message was read out in all Polish churches: on protecting the lives of the unborn, we cannot continue with the current compromise, which allows abortion in three types of cases».

The immediately subsequent events are reconstructed in detail in the article published in «Krytyka Polityczna»: «On 5 July 2016, the so-called “Stop abortion” bill was submitted to the spokesman for the Sejm (the lower house of the Polish parliament). He proposed a total ban on the termination of pregnancy and also established that, in the event of an abortion, both the woman and the individual who carried out the procedure are punished. A mass movement against this law, called “The Black Protest”, immediately awakened the people’s spirits. The symbols of the protest were a black umbrella and a wire hanger – references to the risky methods used in illegal abortions».11See: https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/10812/new-east-women-poland-activism-abortion

As is well known, this debate has reached an international reach, prompting the population of more than fifty countries between Europe, Asia and Australia to sympathize with Polish women and their protests.22In her article You are not alone. The birth of grassroots feminism in Poland, Agnieszka Graff describes her first impressions of this sudden, spontaneous insurrection in Poland: «The feminist graffiti can be read as an invasion of the Church’s terrain – a response to the invasion of the women’s bodies that the Church was enabling. At first, this event shocked and amazed me (a border had been crossed that would have been intransgressible just a year or two ago), but I soon experienced a strange sense of relief, similar to the feeling that accompanies a coming storm after a muggy, stifling day. Yes, it had been hanging in the air, it was inevitable. But what was “it”? Let’s say, perhaps, that it was a certain rupture, an angry breaching of a contract».

But how did we get here? The path of Polish feminism, as well as the presence of women within Polish art, are so uneven that they reflect in a certain sense the history of the country itself. The birth of the first women’s movements dates back to the nineteenth century. To comprehensively understand the issue it’s necessary to frame it within a local context. The true origin of Polish feminism, corresponding to what has been defined as the first three feminist “waves” (historians have identified seven of them in total), coincides with the struggle for national independence. Poland was partitioned between neighboring countries several times, and three times, between 1772 and 1918, it even ceased to exist. The so-called “fourth partition of Poland”, i.e. the aggression of the USSR and Nazi Germany against the country during the Second World War, and the subsequent affirmation, between ’44 and ’89, of the communist regime, effectively kept people far from a mature feminist mentality.

– The first four feminist waves in Poland. Male support for the feminist cause: between support and hypocrisy

In Between Feminism and the Catholic Church: The Women’s Movement in Poland (2005), Małgorzata Fuszara reconstructs the initial stages of Polish feminism through this description: «The first organized group that aimed to improve the position and education of women were the “Enthusiasts”, whose most famous member was Narcyza Żmichowska. The group was active in Warsaw between 1840 and 1850. The Enthusiasts were engaged in a clandestine struggle for independence and were subject to political oppression. Most of the activists were imprisoned and exiled by the Russian authorities, who put an end to the group’s activities. It was not until the 19th century that there were the first signs of progress towards achieving equal rights for women. It was then that the first women’s congresses took place (in Lviv, in 1894, in Zakopane in 1899 and Krakow in 1900 and 1905), to discuss the role and tasks of women, followed later, in 1907, by the foundation of the Polish Society for Equal Rights for Women, among whose objectives there was also the struggle for women’s suffrage».

This early period in the history of Polish feminism is known to have been widely supported by academics. Edward Prądzyński, author of On Women’s Rights (1873) is one of the most emblematic examples of “male” literature of the time in favor of female emancipation. In his book, he exhorts: «A young man, husband, and father! A woman, a charming object of passionate homage and selfish power of yours, today, she is asking for her humanity». Alongside the numerous female activists of the time33Maria Konopnicka, Eliza Orzeszkowa, Zofia Nałkowska, Maria Rodziewiczówna, Paulina Kuczalska-Reinschmit, Gabriela Zapolska, Bibianna Moraczewska, Justyna Budzińska-Tylicka, Kazimiera Bujwidowa, Maria Dulębianka, Maria Komornicka, Iza Moszczeńska, Józefa Sawicka, Cecylia Walewska.

(many of whom criticized and hated by conservatives),44About Eliza Orzeszkowa, K. Długosz, K. Monkiewicz, P. Nowosielska, Poczet feministek polskich, «Przegląd», March 9, 2003: «The conservatives hated her for criticizing blind religiosity and making women rebellious against male domination. She smoked cigarettes, which caused even more spite. She assumed matron poses, referred to the family as the “cornerstone of customs”, while she left her husband, lived alone and had several affairs. “She dared to live her life to the full, so that, at least in her writings, she didn’t want to be perceived as a scandalizer” – Irena Krzywicka commented».

within the rich Polish feminist literary heritage are works by male authors in support of women’s emancipation. However, as Maciej Duda, a researcher at the University of Szczecin has recently shown, many of the official statements of these men were the result of mere hypocrisy. Within many of private authors’ testimonies – such as letters and personal diaries – very different words and emotional tones emerge, such as those expressed by Bolesław Prus. The creator of Emancypantki (The New Woman, 1890-1893) once declared that «the slogans <women’s rights> and <emancipation> disgusted him so much that while he pronounced them, he used to cough».

In the same way as Duda, the researcher Magdalena Gawin demolished the coherence of another historical figure associated with the women’s movement, that of the sociologist Ludwik Krzywicki, whose “inviolable patriarchal power structure” was visible within his own family, as evidenced by his diaries. Krzywicki spread a somewhat malevolent critique of women, stating that they were “unimaginative” and driven by a “trivial ambition”.

On the opposite front – that of men who sincerely supported female empowerment – remains Edward Prądzyński’s precious testimony. He was the author of the great emancipationist work On Women’s Rights (1873), in whose introduction we can understand what was, at the time, the widespread opinion among men about the nascent women’s movement: «Allow me to make a confession. A dozen years ago, in one of the Warsaw high schools, I wore the uniform of my sixth year of school. At the time of recreation, in our circle of friends, a heated dispute arose, which had a woman as its protagonist. Although at the time, there was no talk of equality yet, we continued to discuss the woman. It’s well-known that there is barely a more grateful conversation subject for 16-to-17-year-old gentlemen! We were talking, therefore, about a woman. What her duties should be, what a man could allow himself so that he wouldn’t be blamed for his actions, and for what reasons, women will instead always be inevitably and unconditionally condemned. I remember that these theories, put forward by one of my older colleagues, shocked me so much, that I began to vigorously argue that a moral principle valid for both of them should have been applied. My argument had to be somewhat weak, since I was unable to convince my comrades, provoking in them only ridicule and malicious comments. […] I was quite angry about my friends’ blindness, who disagreed with my way of thinking. I blamed the lack of sufficient arguments the cause of my failure, and at that very moment I decided to arm myself with convincing evidence so that one day I would be able to convince even the most stubborn opponents who were wrong».

– The fifth feminist wave, the two wars and the spread of female talent in the field of creativity

If the first four feminist waves coincided with the partition of the country, the fifth flourished in the period between the two wars (1918-1939) and was much more intense. In 1918, Poland gained independence, and women were accorded the same voting and eligibility rights as men. It was November 28th when, with the decree of Józef Piłsudski, women gain passive and active electoral law. The women elected in the first elections on January 26th, 1919 made up about 2% of the total Polish government. As Fuszara reminds in her essay: «More than eighty different women’s organizations were founded in Poland in the years between the First and Second World Wars. There was a great variety, from professional groups to religious organizations. Also, many women’s magazines and books intended for a female audience were published. Women had their Parliamentary Society, and there were funds and scholarships for women and women’s clubs».

Compared to that of other European countries, the situation of women in Polish high-society families of the time was relatively better. In many cases, women were forced to take the place of men, meanwhile engaged in military operations. Thus, women were holding social roles traditionally attributed to the opposite sex. At the same time, as the scholar Małgorzata Kądziela notes, «The ideal woman was presented as <guardian of the hearth> and educator of the younger generations, according to the spirit of national-Catholic values». Towards this ideal, feminists united to take a step forward. The radical group composed of Irena Krzywicka and Maria Morozowicz-Szczepkowska disclosed, in fact, the goal of liberating women from romantic relationships with men.

In the same period, the field of arts also saw a real revolution, as researcher Diana Poskota-Włodek notes, citing a reference by Morozowicz-Szczepkowska to the «eruption of female talents in every field of creativity». In this regard, it’s important to note that «feminists encompassed outright all women who were cultured, independent and professionally active and almost automatically successful. Not all of them were activists nor did they all consider themselves feminists. […] In Poland, between the 1920s and 1930s, and many years after the wave of Ibsenism and Zapolska’s theatrical premières, promoting the female issue was nothing new. The new thing consisted of the fact that the feminist discourse coincided with real and universal changes, and not only with those presupposed, social and economic, in which women participated in the first post-war period».

As you can easily imagine, the Second World War effectively paused the feminist cause. Forced national unity, aimed at the defense against the invader, inhibited both individual development and any kind of social progress. As Jill M. Bystydzienski notes, women maintained their traditional role as volunteer organizers and educators. Besides, there was the Church’s influence, still very present in Poland today. To understand the nature of this influence, Bystydzienski’s words are still useful: «[During the Second World War] the Church was the only institution, legally existing in opposition to the authorities. As a national institution, it helped to preserve the national identity since more than 90% of the Polish population is Catholic. However, the Catholic church upholds the traditional role of women and teaches them to accept their fate, to be martyrs to their nation, and to family. Furthermore, persistent cultural traditions, which continue to reinforce the subordinate status of women still exist in Poland. These include different forms of male cavalry (for example, hand-kissing as a greeting), and very strong ideals of feminine beauty, passivity, and self-sacrifice».

– The turning point of the communist regime

After the stalemate of the two wars, with the birth of the new communist regime, the situation changed radically. During the communist era, women obtained various advantages more, compared to the past, such as better access to education and the world of work. However, the conquest for rights continued to clash with a highly authoritarian system, effectively revealing all its difficulties. As Kądziela notes in this regard: «The need for a workforce – in the spirit of equality – has promoted the image of woman as a leader at work. According to the communist ideology of “emancipation”, women were seemingly exempt from domestic duties thanks to the institutionalization process of the education of children (preschools, kindergartens, school common rooms). But in reality, due to the unfavorable economic situation, they were obliged to reconcile roles of mothers, wives, and workers».

It’s interesting to note the birth of the women’s organization in 1945, set up by the regime, called “The Women’s Social and Civic League”. Its objectives were the promotion of women’s professional work, assistance in daily life, and educational activities. Such organizations had the purpose of aggregating the needs, and requests for women’s rights, under the sole sign of a complete, and reassuring adherence to regime policies. It’s also evidenced by the complete absence of local, and independent movements for women: «<The Women’s Social and Civic League> was established by the authorities as the only women’s movement, and was created without the direct involvement of women. Like many other organizations, founded in recent years, by the new political authorities, it was treated as an emanation of the imposed power and failed to promote the interests of the group that it was originally meant to represent. Such organizations couldn’t hope for any social backing whatsoever. It was even reflected in the claims of the League activists at the extraordinary League Congress in 1981 when democratization began to take hold, following the founding of Solidarność in 1980. The female members’ speeches contained statements such as: “The corset, which was once put on us, continues to be impeding us”, “We are so weak and defenseless” and “Democracy is impossible without the involvement of women”».

As Bystydzienski rightly notes, «The communist regime passed on, in genes, a deep distrust of achieving gender equality, and feminism. On the one hand, state propaganda has managed to successfully devalue the feminist cause and to sow, an almost unanimous, contempt for Western feminism, presented as a bourgeois concern by wealthy, frustrated, and mainly American, women. On the other hand, during socialism, “gender equality” was taken for granted, although the facts proved otherwise. Thus, women usually didn’t perceive, how necessary feminism was, and many of them developed a real “allergy to feminism”».

– Movements for women from the end of communism to the present day

When the communist system collapsed in 1989, numerous state factories and workplaces suddenly closed, as did kindergartens and nursery schools belonging to them. This event, naturally, deeply affected especially mothers, forced to raise their children and at the same time to go looking for a job in a general situation of uncertainty and instability.

After several years of oppression by the Soviet Union, Solidarność, the Polish union born in 1980 and recognized as a legitimate political party in 1989, finally led Poland to democracy. Not surprisingly, the first local women’s movements were born between 1980 and ’81. It was just a year and a half after the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Women’s Discrimination, through which, the acceding countries «committed themselves to ensure equal opportunities for citizens of both sexes in all spheres of social life». As we know, this purpose, unfortunately, didn’t find full and concrete implementation in Poland, but after 1989, the post-Soviet approach began to intertwine with the western lifestyle. Thus, women learned to shout their voices against every type of inequality and discrimination.

Within the political world, however, after the collapse of communism, the situation of women, unfortunately, didn’t register great improvements. As Fuszara reconstructs: «The low level of women’s participation in power was inherited from the communist period. After 1989 the proportion of women in parliament decreased even further. In response to the situation, initiatives and organizations intending to increase women’s participation emerged. Also, the gap between male and female wages has grown significantly since 1989, and the situation has been offset by the appearance of a new problem that has affected women more than men – unemployment. In response to these problems, several organizations and initiatives have emerged in favor of professionally active women».

At present, the general situation of women isn’t at its best neither – «the law is ineffective in protecting women from domestic violence, pensionable age differs according to sex, there is inequality in the labor market concerning the position and pay, with alarming examples of women seeking employment being asked to take pregnancy tests».

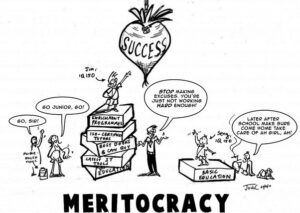

Still from Kądziela’s research, we learn that in a 1999 survey, Polish citizens were asked: «In the event of a job shortage, should men have priority over women?». 52% of the interviewees responded yes, and we shouldn’t be surprised at this result: «In the Polish patriarchal model of society, a woman can work only under the condition that she succeeds in fulfilling her family duties, which means, she has to be efficient both at work and home». Kądziela adds: «Social pressure forces women to take roles traditionally attributed to them sometimes even against their will. The victory of Solidarność, in 1993, brought a consolidation of the opinion that women should retreat from the public sphere. This situation points out another characteristic feature of Polish society, which – in every area of life – zealously rewards activities that relegate women to the private sphere, thus, creating favorable conditions for men to participate in official public life. 74% of the population in Poland agree emphatically that, if a woman wants to be perceived as worthy, she should have children».

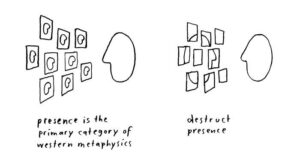

One of the most peculiar aspects of contemporary Polish culture is a profound gap between social practices belonging to the public sphere, generally associated with the official and institutional realm and those associated with the private sphere. Holding this mental system means that, in Polish social conscience, “real life” is blissfully perceived as located outside the official sphere, therefore distant from the discourse of civil rights. All this, of course, contrasts gender rights equalization: «[…] Such an attitude, often proudly called “common sense”, seems to favor the concealment of some arbitrary cultural issues, in particular, those related to gender roles within society. Consequently, it makes their denaturalization almost impossible». Lucyna Kopciewicz notes that one might have the impression that critical reflection still represents this “official” way of thinking, so it is, therefore, not held in high regard, since “official” means “removed from the real-life”».

Between modern, increased women’s awareness, widespread misunderstanding of fundamental feminist principles and preservation of a sort of national holiness in the figure of the “Polish Mother” – a complex combination of the immaculate Virgin Mary, the fearless nurse, obedient wife, tireless worker, and, at the same time, super mother – in recent years tensions within the country have strengthened again. The religious concept of Mother Mary is preserved at all costs by conservatives, as well as, thoughtlessly inculcated in all women, thus causing unimaginable damage, including risks for pregnant women. As Kądziela notes, this «traditional image of the woman as a mother also excludes all the discourses on non-reproductive sexuality», thus spreading an acute contempt for homosexuality within the society.

In this scenario, the pressing influence of the Church on governmental decisions regarding women’s rights, with the complicity of the current far-right policy (towards which the country veered in 2015), has generated among people, a more than understandable, mass irritation. The first and largest mobilization of this kind, “The Black Protest”, took place in 2016. On that occasion, women took to the streets to defend their right to independently decide on the termination of pregnancy and stood against current Polish laws on abortion, still among the most restrictive in Europe. Instantly, women started creating grassroots organizations in a flash. The restricted access to an abortion caused the emergence of supportive groups, offering guidance with family planning and birth control. The support of many, more or less known, Polish artists has been very relevant as well.

– The role of art in contemporary feminist protests

A famous Polish artist, Katarzyna Kozyra, recently compiled a report on the scarce presence of women within the art academies in Poland, titling it significantly Miserable chances for promotion (Marne szanse na awanse, 2015): «The academies of Fine Arts are extremely feminized as a place of study, and incredibly masculinized as a workplace. What struck us most is the clear discrepancy between these two career phases, with a disproportion that is comparable only to schools of theology».

Although even today, in the world of Polish art, there is no true gender equality, many female artists have, through their research, fought for equal rights over decades. Several male artists, such as Zbigniew Libera, have also paid attention to this theme. In the video How to train little girls (1987), he emphasizes the role that social education plays in sedimenting gender roles in Poland.

Polish art has expressed support for women’s movements (and vice versa) on several occasions, during protests and collective initiatives. To name the recent one, #bananagate was a protest that arose in 2019, following the decision, taken by the director of the National Museum in Warsaw, to remove from the museum the female cause-related works. Dorian Batycka reports in the article for «Hyperallergic»: «The scandal broke after Polish media outlet “Onet” announced that the National Museum in Warsaw decided on April 26 to remove Natalia LL’s Consumer Art (1973), Katarzyna Kozyra’s Appearance of Lou Salome (2005), and Aleksandra Kubiak and Karolina Wiktor’s Part XL. Tele Game (2005), citing an anonymous letter received by the museum’s director, Jerzy Miziołek, from a concerned mother who characterized her son’s visit to the museum as “traumatic”». It’s no coincidence that censored works feature independent women, capable of threatening, with the sole force of their affirmation, the foundations of a deeply patriarchal nation. In response to this event, still in April 2019, thousands of people took to the streets, each publicly holding and eating a banana – a representative object of the work of Natalia LL, which she previously used symbolically to support the feminist cause, and as a reference to the capitalist system that Poland has been implementing for the past thirty years.

The subversive charge of Polish art aligned with modern movements of female emancipation is also found in the context of musical culture. At this point, the postpunk duo SIKSA, composed of Alex Freiheit and Piotr Buratyński, comes into play.

– The feminism of the post-punk duo SIKSA

«Oh God, oh God, they were so shiny | but the Polish jackboots are gonna shine better! | Because in Poland everything is better | Polish cocks | Erected upright in front of Ukrainian girls in 2018 | in front of those Filthy Ukrainian girls | and those won’t be the jackboots made by Hugo Boss | but by Maciej Zień | God damn it».

(

SIKSA, Polityk, ale kobieta (Politician, but a woman), Stabat Mater Dolorosa, 2018)

One of the most interesting aspects of this heterogeneous project placed somewhere between punk, theater, performance, and psychodrama, is that, on the one hand, all the feminist historical legacy of the country converge in it, on the other, it raises many of the most current, widespread reflections associated with the women’s movement.

The band presents a rather peculiar style, with a female voice – that of Alex – brought to exasperation, through continuous shouts, and accompanied by the constant rhythm of a bass – played by Piotr.

Messages conveyed by SIKSA are a form of proper social activism, expressed and obtained through the simultaneous mixing of music, fashion, visual arts, workshops, and poetry. Occasionally, SIKSA engages in film-making, like in Stabat Mater Dolorosa, directed in 2018 by Piotr Macha.

The duo has spoken about their art on several occasions, like in this Buratyński’s declaration: «As punks, we take punk, and do with it what it was intended for us. To destroy petty-bourgeois habits, knock people out of the “comfort zone”. Even if it’s not a matter of text, but our “formal clumsiness”, which cannot be separated from the words of Alex, content, and which is closely connected with the whole message we transmit». And again: «Thanks to the fact that we are only a bass and a singer, at the same time we reject and fascinate people; we act a bit like the Verfremdungseffekt (aka “alienation effect”, “estrangement effect”) in the Brecht theater, yet we attract them, we make them curious. Bass, voice, a minimalist performance».

SIKSA’s songs relate to the feminist cause, Polish history, contemporary society, as well as the private life of an average Pole. One aspect that certainly stands out is female anger, expressed with the tone of voice and with texts, that accompany every song. Speaking of anger, Agnieszka Graff describes the entry, into the contemporary Polish culture and art, of a new figure, that of the furious woman: «This new female entity is angry, shameless, threatening and loud. Importantly, for some time now, it has ceased to be perceived as marginal or weird. It may arouse indignation, but it’s no longer being dismissed. A feminist rebellion is taking place at the very heart of Polish culture, where up until now there had been silence – in the place where religion, national identity and corporeality meet. Until now, few had even peered into this space; now, all of a sudden, there’s uproar. It cannot be drowned out or silenced. Something has changed irreversibly».

The song Mariusz, wracaj do domu! (Mariusz, come back home!) refers to the video that Anna Kamińska, ex-wife of the parliamentarian Mariusz Kamiński, published following her divorce, in the hope of convincing the man at all costs to return home, appealing to values of the Christian tradition. The result of such appropriation by SIKSA is the desperate, and, at times grotesque, singing of a woman abandoned by her man, who repeats “come home”, intending to save the appearances of a conventional family model, which, due to cultural conditioning, relegates women to a completely marginal role.

When it comes to gender roles’ disproportion within Polish society, researcher Jolanta Brach-Czaina notes that «We live in a male civilization that breaks the bonds between women, and erases the traces of these relationships. Women don’t have their surnames. They’re assigned to male families. It’s an old social fact, and no importance is given to it. It’s said that it cannot be changed. Well, one can, at least, conclude that it’s not a neutral, but deeply discriminatory practice. Women are swept away by history».

In other words, it is, as if the condition of limited freedom, to which Polish women are subject, was generally perceived as a completely natural condition, intrinsic to their destiny and, therefore, socially accepted. Against this normalizing vision of female oppression, SIKSA, in the words of Alex Freiheit, expresses all its dissent: «I didn’t invent myself from the outer space. I am what I experienced myself, the people around me, apparently, other girls as well. Yes, I torture myself and others, I avenge myself, I am like Uma in Kill Bill. This is the therapy I have come up with. It’s a therapy that also works for others, especially for girls». And she adds: «SIKSA is not a project. It’s a long-term therapy, it’s a performance, it’s punk – it’s ACTION, finding yourself in both comfortable and uncomfortable situations. Each concert leaves something different in me. […] It’s my personal, original idea to recover after the rapes, a despotic father, parents who cheat on each other, male humiliation, psychological manipulations. It’s necessary to pay attention to the fact that, what someone easily laughs at, will affect other people, because laughing and trolling on the Internet often corresponds to a particular and serious problem».

The main meaning of the word “siksa” in Polish is that of a “young girl” – old enough to have her own opinions, but still perceived as a naive girl or, at most, a teenager. It can be used in a derogatory sense, to indicate a young, childish woman, whose opinions are not to be taken into consideration. Also, it can be used by a wife, to maliciously name a much younger lover of her husband. However, the word “siksa” is applicable also as a kind of endorsement of independence. Its positive meaning is expressed in the way that grandmothers refer to a particularly lively, chatty and impertinent granddaughter. Finally, a further meaning of the term derives from the Yiddish “šiqsah”, “non-Jewish girl” (derivative of “šekes”, “disgust”).

In its general representation, SIKSA plays various roles by lending its voice to different identities, through the constant filter of irony, as when, referring to the declaration of a famous Polish TV star, she says: «Ladies and gentlemen… I have never been, I am not, and I will never be a feminist because I want to be a beautiful woman, to have children, a house and a husband». (SIKSA, Marina Abramovic, in Stabat Mater Dolorosa, 2018)

Today, the fundamental problem of feminism in Poland is its interpretation, both by the institutions and on the social and cultural level. Feminism is considered the antipodes of happy family life. Furthermore, it’s seen as dangerous for the unity of Poland and perceived as a promoter of values, which are contrary to the patriarchal structure, on which the life of the country is based. It’s within this scenario, so negatively characterized, that the disruptive force of artists and movements, such as SIKSA, can perhaps act to undermine the current social structure with the aim of real emancipation of women and complete equality of rights: «Our country will regain its dignity, when all, without training, will chew your penises off. And these stupid cunts, who say: “But I’m not a feminist… Just a patriot and I’m proud to have a boyfriend who is a hunter… and I’m not a feminiiiiiiissssst”. In fact, you’re not – YOU STUPID CUNT!» (SIKSA, Agrest/Godność (Gooseberries/Dignity), Punk ist tot, 2016).

[3] Maria Konopnicka, Eliza Orzeszkowa, Zofia Nałkowska, Maria Rodziewiczówna, Paulina Kuczalska-Reinschmit, Gabriela Zapolska, Bibianna Moraczewska, Justyna Budzińska-Tylicka, Kazimiera Bujwidowa, Maria Dulębianka, Maria Komornicka, Iza Moszczeńska, Józefa Sawicka, Cecylia Walewska.

[4] About Eliza Orzeszkowa, K. Długosz, K. Monkiewicz, P. Nowosielska, Poczet feministek polskich, «Przegląd», March 9, 2003: «The conservatives hated her for criticizing blind religiosity and making women rebellious against male domination. She smoked cigarettes, which caused even more spite. She assumed matron poses, referred to the family as the “cornerstone of customs”, while she left her husband, lived alone and had several affairs. “She dared to live her life to the full, so that, at least in her writings, she didn’t want to be perceived as a scandalizer” – Irena Krzywicka commented».

[5] Among many, there are the following: Woman’s Independence (1870) by Adam Wiślicki, On the so-called <female> issue from the position of the natural sciences (1897) by Benedikt Dybowski, On Women’s Work from the Economic Standpoint (1874) by Leon Biliński, Man and Woman (1918) by Ignacy Radliński, Consistory Virgins (1929) and Women’s Hell(1930) by Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński, as well as contributions from Edward Dembowski, Piotr Chmielowski, Hipolit Skimborowicz, Kazimierz Kelles-Krauz, Wacław Nałkowski, Bolesław Prus, Aleksander Świętochowski, Odo Bujwid, Napoleon Cybulski, Leon Petrażycki, Antoni Lange.

[6] Reported in Maciej Duda, (Auto)biography as an instrument of research in area of women’s equal rights. A contribution to the discussion.

[7] In M. Kądziela, Society Versus Art: Reflections About Feminism in Poland.

[8] Irena Krzywicka expresses an acute dissatisfaction with the general attitude of the women of the time: «I would like so much to have a good opinion of women! They are intelligent, have healthy life energy. So how come they are so immature, cowardly, clumsy and obedient. When will they stop? In ten years? Twenty? Please let me know when it will be possible to communicate with you».

[9] In D. Poskota-Włodek, The collusion of women? Feminist stagings in the Polish theater of the interwar period, 2015.

[10] Worth mentioning, among others: Bronisława Ostrowska, Kazimiera Iłłakowiczówna, Maria Wielopolska, Zofia Nałkowska, Pola Gojawiczyńsa, Maria Kuncewicz, Halina Krahelska, Elżbieta Szemplińska, Wanda Wasilewska, Wanda Melcer, Stefania Okołów-Podhorska, Kazimiera Muszałówna, Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska, Magdalena Samozwaniec, Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, Jadwiga Migowa.

[11] In Bystydzienski, The feminist movement in Poland: Why so slow?, 2001.

[12] In M. Kądziela, Society Versus Art: Reflections on Feminism in Poland.

[13] Fuszara, quote.

[14] In Bystydzienski, The feminist movement in Poland: Why so slow?, 2001.

[15] Kądziela, quote.

[16] Fuszara, quote.

[17] M. Kądziela, quote.

[18] Kądziela, quote.

[19] To mention only a few of them: Katarzyna Kozyra, Ewa Partum, Katarzyna Kobro, Monika Zielińska (Mamzeta), Katarzyna Górna, Dorota Nieznalska, Alicja Żebrowska, Krystyna Piotrowska, Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Alina Szapocznikow, Julita Wójcik, Iwona Demko, Paulina Ołowska, Elżbieta Jabłońska, Grupa Sędzia Główny, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Ewa Juszkiewicz, Anna Baumgart, Natalia LL, Agata Zbylut.

More on Magazine & Editions

Magazine , LINGUAGGI - Part II

MUTAZIONI

La materialità del corpo, le sue trasformazioni e l’esperienza incarnata del cinema.

Magazine , LINGUAGGI - Part II

I LOVE DICK. O del femminile

Il Female Gaze di Joey Soloway su corpo, desiderio, spazio e soggettività.

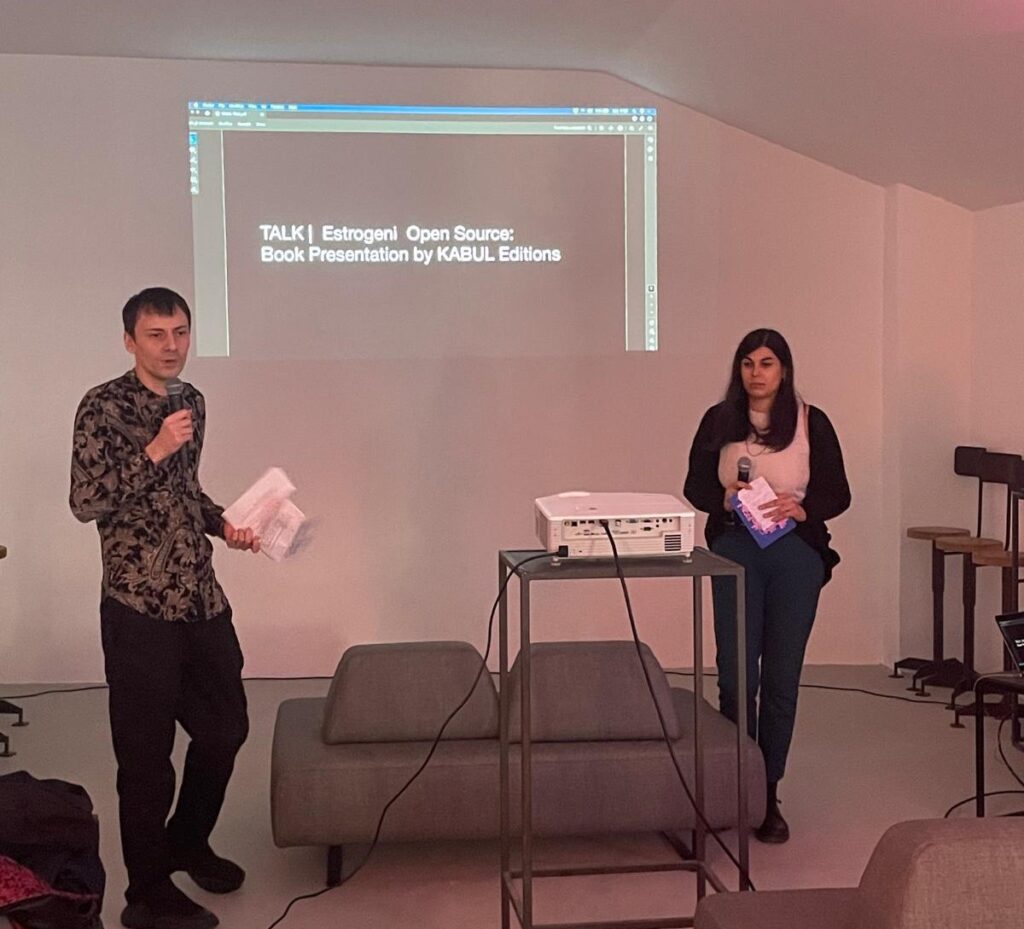

Editions

Estrogeni Open Source

Dalle biomolecole alla biopolitica… Il biopotere istituzionalizzato degli ormoni!

Editions

Embody. L’ineffabilità dell’esperienza incarnata

Il concetto di coscienza incarna per parlare di alterità e rivendicazione identitaria

More on Digital Library & Projects

Digital Library

Imitazione di un Sogno

Esplorazioni filosofiche e sensoriali tra sogno e realtà.

Digital Library

Immagine della vittima ed emancipazione: l’art-community ucraina e il femminismo

Viaggio nell’Ucraina femminista: ridefinizione di una nuova coscienza e riappropriazione del corpo attraverso l'arte contemporanea.

Projects

Earthbound. Ecologie di genere – Il video

Il video del talk "Earthbound. Ecologie di genere" in collaborazione con TCC e Careof

Projects

Il ruolo della donna nelle istituzioni d’arte Latino-Americane (#artissimalive)

Fernanda Brenner, Julieta Gonzáles e Abaseh Mirvali, con la moderazione di Federico Luger, ripercorrono la loro carriera.

Iscriviti alla Newsletter

"Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. But sharing isn’t immoral – it’s a moral imperative” (Aaron Swartz)

-

Dobrosława Nowak è scrittrice, ricercatrice, artista e curatrice. Laureata in Fotografia (2013) all'Università dell'Arte di Poznań (Polonia) e in Psicologia (2015) all'Università di Adam Mickiewicz a Poznań. Nel 2018 ha frequentato il corso "Ultime Tendenze nelle Arti Visive" all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera. Scrive d'arte per varie riviste in inglese, italiano, polacco e francese. Nata in Polonia, vive e lavora a Milano.

J. Bystydzienski, The feminist movement in Poland: Why so slow?, 2001.

K. Długosz, K. Monkiewicz, P. Nowosielska, Poczet feministek polskich, «Przegląd», 9th march 2003.

M. Duda, (Auto)biography as a material in the study of the history of women’s equality. A contribution to the discussion.

M. Fuszara, Between Feminism and the Catholic Church: The Women’s Movement in Poland, 2005.

M. Kądziela, Society Versus Art: Reflections About Feminism in Poland.

N. Kriki, Poland for Beginners: Explaining Black Protests, «Krytyka Polityczna & European Alternatives», 19th may 2017.

D. Poskota-Włodek, Collusion of women? Feminist stagings in the Polish theater of the interwar period, 2015.

KABUL è una rivista di arti e culture contemporanee (KABUL magazine), una casa editrice indipendente (KABUL editions), un archivio digitale gratuito di traduzioni (KABUL digital library), un’associazione culturale no profit (KABUL projects). KABUL opera dal 2016 per la promozione della cultura contemporanea in Italia. Insieme a critici, docenti universitari e operatori del settore, si occupa di divulgare argomenti e ricerche centrali nell’attuale dibattito artistico e culturale internazionale.